The Credit Crunch #44

Howard Marks on Easy Money, Fundraising News from Ares, Apollo and Infranity

Welcome back to the 44th Credit Crunch.

Read my previous articles here, subscribe here and please share this.

I had planned to share my analysis on fund sizes this week. Unfortunately, Howard Marks released a memo that I thought was a lot more interesting.

If you’re interested in the fund size analysis then like this post and I’ll share it with you directly.

📚Howard Marks : Easy Money (Part one)

These are some of my favourite parts of Howard’s latest memo. I’d highly recommend that you read the memo in full (here).

An analogy for the low interest rate world 🌍

I likened the effect of low interest rates to the moving walkway at the airport. If you walk while on it, you move ahead faster than you would on solid ground. But you mustn’t attribute this rapid pace to your physical fitness and overlook the contribution from the walkway.

In much the same way, declining and ultra-low interest rates had a huge but underrated influence on the period in question. They made it:

easy to run a business, with the stimulated economy growing unabated for more than a decade;

easy for investors to enjoy asset appreciation;

easy and cheap to lever investments;

easy and cheap for businesses to obtain financing; and

easy to avoid default and bankruptcy.

In short, these were easy times, fueled by easy money. Like travelers on the moving walkway, it was easy for businesspeople and investors to think they were doing a great job all on their own.

The effects of low interest rates

Howard summarises ten effects that happen when interest rates are low. These are three of my favourites:

Low interest rates encourage risk taking, leading to potentially unwise investments

Low interest rates create a “low-return world” marked by paltry prospective returns on safe investments. At the same time, investors’ required returns or desired returns typically don’t decline meaning investors face a shortfall. The ultra-low returns on safe assets cause some investors to take additional risks to access higher returns. Thus, these investors become what my late father-in-law called “handcuff volunteers” – they move further out on the risk curve not because they want to, but because they believe it’s the only way to achieve the returns they seek.

In this way, capital moves out of low-return, safe assets and in the direction of riskier opportunities, resulting in strong demand for the latter and rising asset prices. Riskier investments perform well for a while under these conditions, encouraging further risk taking and speculation:

In all these ways, the return increments associated with longer-term, riskier, or less-liquid assets can become inadequate to fully compensate for the increase in risk. Nevertheless, the low prospective returns on safe securities cause investors to look past these factors and lower their standards, encouraging speculation and causing questionable investments to be made in pursuit of higher returns.

Low interest rates cause investors to prioritise “desired returns” over credit standards. This results in above-average investment in long-dated or illiquid assets. These investments are based on overly optimistic or unrealistic expected future values. This strategy works in the short run. Unfortunately when interest rates rise, these assets experience significant repricing due to the increased discounting of future cashflows.

Howard highlights that this effect is well known and dates back as far as 1867. Austrian economists call this “Malinvestment”.

Malinvestments are badly allocated business investments resulting from artificially low interest rates for borrowing and an unsustainable increase in money supply. (Wiki)

This is similar to Kyle Harrison’s summary of the Venture Capital markets in recent years.

One of the most un-dealt with ramifications of a 13-year bull market is the institutionalized belief in "the greater fool." People can make money, not because a business is sound, but because there is always someone else down the line who will buy you out. And that was true for 10+ years! (Full article here)

Low rates enable deals to be financed readily and cheaply

Low rates make people more willing to lend for risky propositions. Providers of capital vie to be the one who gets the deal. To compete for deals, the “winner” must be willing to accept low returns from possibly questionable projects and reduced safety, including weaker documentation. For this reason, it’s often said that “the worst of loans are made at the best of times.”

Many managers have commented on this in recent months.

KKR wrote:

We think there will be a strong bifurcation and increasing dispersion between lenders who balanced risk in the good times by lending to high-quality, larger companies with resilient business models and capital structures and those who did the opposite.

Blackstone wrote:

We believe this higher-for-longer rate environment creates meaningful dispersion amongst managers because not all private credit, and not all lending, is the same.

Pimco wrote:

We expect the current interest rate environment to put pressure on much of the existing stock of credit – particularly corporate and commercial real estate-related credit that was originated in an environment of abundant supply and low interest rates

Low interest rates encourage greater use of leverage, increasing fragility

Borrowed money – leverage – is the mother’s milk of rapid expansion and speculation. In my memo It’s All Good (July 2007), I compared leverage to ketchup: “I was a picky eater when I was a kid, but I loved ketchup, and my pickiness could be overcome with ketchup.” Ketchup got me to eat food I otherwise would have considered inedible. In much the same way, leverage can make otherwise unattractive investments investible. Let’s say you’re offered a low-rated loan yielding 6%. “No way,” you say, “I’d never buy a security that risky at such a low yield.” But what if you’re told you can borrow the money to buy it at 4%? “Oh, that’s a different story. I’ll take all I can get.” But it must be noted that cheap leverage doesn’t make investments better; it merely amplifies the results.

In times of low interest rates, absolute prospective returns are low and leverage is cheap. Why not use a lot of leverage to increase expected returns? In the late 2010s, money flowed to both private equity, given its emphasis on leveraged returns from company ownership, and private credit, which primarily provides debt capital to private equity deals. These trends complemented each other and led to a significant upswing in levered investing.

But in the last decade, some companies acquired by private equity funds were saddled with capital structures that failed to anticipate the increase in interest rates of 400-500 basis-points. Having to pay interest at higher rates has reduced these companies’ cash flows and interest coverage ratios. Thus, companies that took on as much debt as possible – based on their former levels of earnings and the prevailing low interest rates – may now be unable to service their debt or roll it over in a higher-rate environment.

Finally, all else being equal, the more leverage that’s piled on a company, the lower the probability it’ll be able to survive a rough patch. This is one of the foremost reasons for the adage “never forget the six-foot-tall man who drowned crossing the stream that was five feet deep on average.” Heavy leverage can render companies fragile and make it hard for them to get through the proverbial low spots in the stream.

This effect can be seen in the S&P’s December 2023 Middle Market analysis (Link). Below are the Top 10 sectors by percentage of companies with less than 1.0 interest coverage ratios. Almost half of the companies in the software sector have an interest coverage ratio of less than 1.0x.

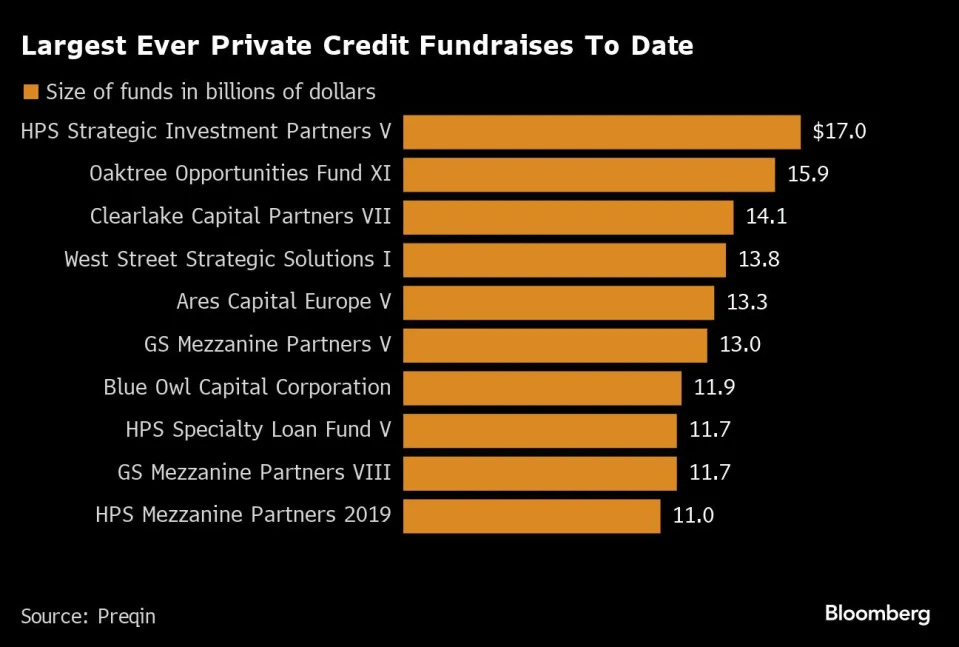

📊 Chart of the Week

Bloomberg have some context ahead of Ares’ latest European fund. Ares’ fund will be ~30% larger than the current largest private credit fund, if accurate (See below for more details).

💰Fundraising news

Ares, a Los Angeles-based alternative investment manager, is reportedly closing its ~$22 billion European direct lending fund VI. This would make it the world’s largest direct lending fund (See below). The fund lends directly to mid-market and large-cap companies to support growth, acquisitions, and refinancings. The team primarily focuses on companies in defensive industries with high free cash flow. More here

Apollo, a New York-based investment manager, is reportedly fundraising a $2 billion Credit Secondaries fund II. Apollo is aiming to become the leader in Credit Secondaries. The size of the latest fund will allow them to source and execute opportunities unavailable to many other secondary funds. Apollo launched the strategy in 2021 with a first fund of $1 billion. More here, here, and here

Read more about why Apollo ❤️ private credit (here)

Infranity, a Paris-based asset manager, launched its ~$1.6 billion Senior Infrastructure Debt Fund IV. The fund lends to European infrastructure assets. It is an Article 8 fund and focuses on lending to businesses that address challenges facing society. These include energy transition, green mobility, the digital transition, and the improvement of social infrastructure in the health and education. Infranity has invested ~€7 billion across more than 70 transactions since 2018. More here, here, and here